You could draw a caricature of his face with little more than a hearty stroke for the jawline and a few exclamatory dots: two for the piercing eyes and one for that magnificent, trademark dimple.

Kirk Douglas, who died on Feb. 5 at age 103, defined the ideal manly-man persona of the 1950s, often giving electrically appealing performances while playing less-than-exemplary characters.

Douglas’s most famous role may be that of the slave who became a rebel leader in ancient Rome, in Stanley Kubrick’s Spartacus (1960). It’s an admirable performance in a noble part. But Douglas could be even more charismatic in his bad-boy roles — as, for example, the scrappy, opportunistic prize fighter Midge Kelly in Champion (1949).

In a career spanning, remarkably, nearly 60 years — mostly in the movies but occasionally on TV — he never shied from playing untrustworthy characters, often with a wink. And he was one of our last surviving links to Old Hollywood and a studio system that rooted out and groomed stars for our pleasure.

Douglas was born Issur Danielovitch in Amsterdam, New York, in 1916, the middle child in a family of seven children — and the only boy. His parents were Russian Jewish immigrants who had fled the pogroms and were unable to read or write; he would later name his production company after his mother, Bryna. Douglas did well in school and wrestled competitively in college, at St. Lawrence University. But he found his true calling after earning a scholarship to the American Academy of the Dramatic Arts. After graduation, he appeared in a few Broadway productions before enlisting in the Navy in 1941, where he was tasked with hunting down Japanese submarines during World War II.

Douglas was initially aiming for a career in the theater. “I had never even considered being a movie actor,” he wrote in his 1988 autobiography, The Ragman’s Son. “My image of a movie actor was someone tall and gorgeous, and I had never thought I fit the bill.” But after his return from the war, Lauren Bacall, an old schoolmate, got him the screen test that led to his first film role, opposite Barbara Stanwyck in The Strange Love of Martha Ivers (1946). Just a few years later, he earned an Academy Award nomination for his performance in Champion, a small-budget film that proved enormously popular with audiences. It also helped make him a star.

In Champion, Douglas plays a boxer who often behaves badly, especially with women: He leaves his nice-girl wife (played by Ruth Roman) just moments after her father forces the two into a shotgun wedding. Later, he cruelly smooshes the clay study of him that his lover (Lola Albright), a sculptor, has labored over. But as a fantasy of the type of guy a woman should never fall for in real life, Douglas’s Midge Kelly is perfect: His wiry build and swooping pompadour are part of his hardscrabble virility. Particularly in the context of all that’s been written about the male gaze in cinema, we pay scant attention to the way movies objectify men, and Douglas was practically built for objectification. In Champion, he’s lit and shot in a way that courts desire: You can’t not notice his extra-long eyelashes, or that cleft chin straight out of art deco statuary. You’re not supposed to approve of Midge, but you’re free to fall into a kind of love with him, at the safe remove cinema grants us.

Douglas wasn’t just an actor; he was a walking fantasy of 1950s masculinity, sometimes the toxic kind and sometimes a type far more exemplary. He’s delightful to watch as a corrupt, backbiting movie producer In The Bad and the Beautiful (1952), one of three films he made with director Vincente Minnelli. That role earned him his second Academy Award nomination.

In another Minnelli film, Lust for Life, Douglas plays Vincent Van Gogh — and once again, he was nominated for, but didn’t win, the Best Actor award. (He received an honorary Oscar in 1996.) In Lust for Life, Douglas is in some ways all wrong: He’s good at capturing the troubled painter’s sharp edges, less so at framing his vulnerability. Still, the performance is fascinating to watch, particularly to see how Douglas, an actor with swagger to spare, suggests Van Gogh’s awkwardness in processing emotional information (as opposed to visual information, which he had no trouble with). Douglas is terrific at capturing those synapses of bewilderment, those moments when Van Gogh just couldn’t figure out what to make of other people. His jagged bursts of awkwardness are both jarring and affecting, particularly in the context of the movie’s big-budget gloss.

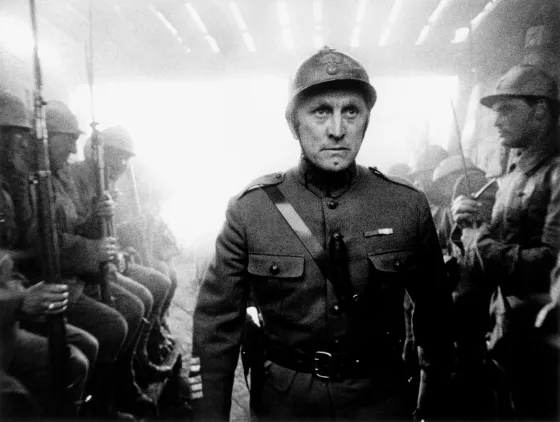

In 1957, Douglas starred in the war drama Paths of Glory, made by a not-yet-famous director named Stanley Kubrick. A few years later, Douglas would hire Kubrick to take over the blockbuster epic he was producing, after the original director, Anthony Mann, had been ousted. Spartacus, with Douglas as its star as well as producer, was an embattled project from start to finish, but it stands as one of the actor’s most enduring pictures.

Douglas would continue to work through the 1960s, ’70s, and ’80s: He appeared in two films by Brian De Palma, one a thriller (The Fury, 1978), the other a comedy (Home Movies, 1979). In 1986, he teamed with his old friend and colleague Burt Lancaster for the gangster comedy Tough Guys. In a 1996 episode of The Simpsons, he provided the voice of Chester J. Lampwick, the aged nutter who invented cartoon violence, but Spartacus was the role that rounded off Douglas’ true golden era. As he himself said in 2015, in an interview included as a special feature in that year’s DVD release of the film, “I have made 90 movies. I don’t think anyone will remember 10 of them. I think I can remember 10 of them. But one everybody can remember is Spartacus.”

Spartacus, as Douglas plays him, is the essence of 1950s-style masculine nobility. He begins life as a slave and ends as a martyred hero. In between, he stands up to authority (in the form of Laurence Olivier’s Roman bigwig Crassus); he becomes a devoted father and husband (his wife is former slave girl Varinia, played by Jean Simmons); and in a complex gesture of mercy, he kills the man who is like a son to him (Tony Curtis’s Antoninus). Douglas, in his early forties at the time, was the ultimate ancient-Roman beach god, virile in his rough mini-tunic, invincible in his warrior’s getup, dashing in the flagrantly homoerotic underpants outfit he wears in the gladiators’ ring. You can laugh at all of it, or most of it—but Douglas’s hold on this character is so earnest and steadfast that it’s hard to take your eyes off him. The performance is a triumphant laurel wreath of determination.

Spartacus is noteworthy for other reasons, too: Howard Fast, the author of the novel on which the movie was based, had been hired to write the screenplay, but his first draft was dismal. Douglas took the opportunity to hire the writer he really wanted, the extraordinarily gifted Dalton Trumbo, a member of the Hollywood 10. Trumbo had spent a year in jail, beginning in 1950, for his earlier affiliation with the Communist party. After his release, he was forbidden to set foot on any studio lot; he’d been just getting by, writing scripts under assumed names for very small fees.

Douglas hired Trumbo, paying him what he was worth, which might have been enough. But when it came time to decide how the screenwriter’s credit should be handled, Kubrick ventured that he should be the one to get it. Appalled that Kubrick would want to claim credit for a script he hadn’t written, Douglas decided Trumbo should, for the first time in a good 10 years, be credited under his own name, a seemingly small act that helped redress some of the wrongs done to Hollywood writers by the House Un-American Activities Committee.

“I wasn’t thinking of being a hero and breaking the blacklist,” Douglas wrote in his autobiography. “It wasn’t until later that I realized the significance of that impulsive gesture. I was just thinking, how unfair for someone to say, ‘Put my name on it. Let me get the credit for someone else’s work.’”

Spartacus won four Academy Awards and made more money for Universal than any previous film in the studio’s history. Douglas was probably right: Of all his films, it’s the one just about everybody remembers. In all of Hollywood, there were certainly bigger stars and more nuanced actors. But Douglas — so filled with un-dimmable bravado, so unabashedly masculine — stood tall on his own. There is only one Spartacus.