It took eight hours for a doctor to see Wu Chen’s mother after she arrived at the hospital. Eight days later, she was dead.

The doctor was “99% sure” she had contracted the mysterious pneumonia-like illness sweeping China’s central city of Wuhan, Wu says, but he didn’t have the testing kit to prove it. And despite the 64-year-old’s fever and perilously low oxygen levels, there was no bed for her. Wu tried two more hospitals over the next week, but all were overrun. By Jan. 25, her mother was slumped on the tile floor of an emergency room, gasping for air, drifting in and out of consciousness. “We didn’t want to see my mom die on the floor, so we took her home,” says Wu, 30. “She passed the next day.”

Because she did not want a spell in jail for dissent to compound her grief, Wu asked TIME to refer to her by a pseudonym–a reasonable request and one that carries with it a measure of what each virus death means to the People’s Republic of China. The novel coronavirus known as 2019-nCoV threatens more than the 24,000 people known to be infected as of Feb. 4 or the 492 it has killed. It also looms over the national rejuvenation project of President Xi Jinping and the rigid, top-down rule being tested by all that the disease brings with it, including distrust in a population the government pledged to keep safe. Since China belatedly acknowledged the severity of the outbreak, every organ of the Chinese state has been harnessed to enforce an unprecedented quarantine on 50 million people across 15 cities. China’s government has unleashed a 1 billion yuan ($142 million) war chest to fight the outbreak amid a frenzy of construction work that, among other feats, erected a 1,000-bed hospital in just 10 days. That there was no cot for Wu’s mother may be understandable, given the time it took to comprehend the disease and how quickly it spread. But what to make of a government that cannot abide the grief of a daughter who took her ailing mother home rather than see her die on a hospital floor?

Transparency is essential to public health. But in China, doctors who reported the reality of the outbreak have been arrested for “spreading rumors.” Officials were pictured pocketing supplies meant for frontline medical staff, who were reduced to cutting up office supplies for makeshift surgical masks. Meanwhile, the ruling Chinese Communist Party (CCP) has already started leveraging the crisis for propaganda by lionizing cadres leading containment efforts. “No crisis is too deadly that they can’t take a time-out to promote the party through manipulation of it,” says Scott W. Harold, an East Asia expert at the U.S. policy think tank Rand Corp.

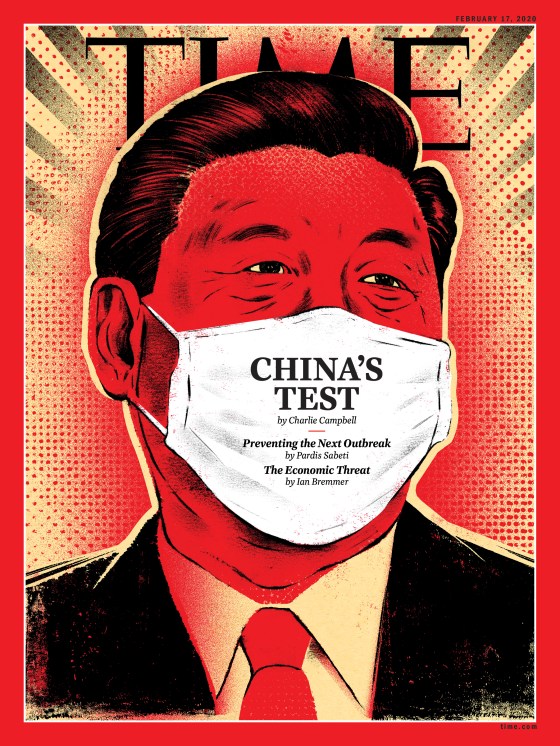

In the fall of 2017, Xi took the podium at Beijing’s Great Hall of the People to claim that China’s version of one-party autocracy offered an option for “countries that want to speed up their development while preserving their independence.” Western democracy was messy and flawed, the argument went. In the years since that speech, China’s hubris has grown, nurtured by the tumultuous U.S. presidency of Donald Trump and the disintegration of the multilateral world order. But the coronavirus crisis threatens to rattle China’s authoritarian apparatus. “A major test of China’s system and capacity for governance” senior party chiefs called it on Feb. 3.

The 2019-nCoV outbreak is infecting some 2,000 people daily in China and has spread to at least 25 countries. The World Health Organization (WHO) declared it a “global health emergency.” And the fear is not limited to health. Global commerce now hinges on China’s $14.55 trillion economy, which in turn is governed by an opaque, authoritarian regime tightly coalesced around one man. Xi, burnished by a resurgent cult of personality, has amassed more power than any Chinese leader since Mao Zedong. He has leveraged Beijing’s economic clout to forward ambitions at home and abroad but also has struggled as no previous leader. “Since Xi came to power, problem after problem have occurred on his watch that he seems unable to effectively manage,” says Jude Blanchette, a China analyst at the Washington-based Center for Strategic and International Studies. These include popular unrest in semiautonomous Hong Kong, a disruptive trade war with the U.S. and now an unfolding health crisis.

For decades, the sales pitch for China’s single-party rule was the superior performance of its political system when faced with both short-term crises and long-term challenges. It built thousands of miles of high-speed rail and helped drag hundreds of millions of people out of poverty. By 2022, McKinsey predicts 550 million Chinese will be able to call themselves middle class–about 1.5 times the current U.S. population. Still, that benevolent narrative has deteriorated under Xi. Now the coronavirus threatens to undermine further his mission to have China stake out the next century as America did the last.

In 2019, China overtook Soviet Russia as history’s most enduring communist state. The seven-decade longevity of the CCP can be attributed in no small part to abandoning great chunks of Marxist-Leninism; instead of centralized planning and top-down targets, China embraced markets and devolved considerable power to its regions and cities. Local party bosses were encouraged to make bold decisions to boost the local economy, like setting up heavily subsidized means of production.

As a result, China boomed but also became a network of little fiefdoms and power centers, where local bosses vied for influence and corruption flourished. Xi came into power in 2012 convinced rampant graft posed an existential threat to the party. To him, only an ideological renaissance coupled with an anticorruption crusade could save China from going the way of the Soviet Union.

A bland apparatchik by reputation, Xi climbed the career ladder as a provincial bureaucrat, eventually emerging as a compromise candidate for the post of China’s top leader. His lack of a power base led party elders to believe he would remain malleable and easy to control. Global leaders hoped he might push through long-awaited economic and social reforms.

They were wrong. Soon after taking power, Xi announced his “China Dream” of a grand national rejuvenation, later speaking about returning China to “center stage of the world.” Far from embracing Western-style market reforms, Xi calcified state control over the economy and stocked its bureaucracy with flunkies and yes-men. Today party zealotry permeates all of Chinese society. The head of China’s national Film Bureau has ordered movies “must have a clear ideological bottom line and cannot challenge the political system.” China’s journalists have been instructed to follow “Marxist news values.” Artists can only produce works that “serve the people and socialism.” One advertisement for sperm donors required applicants ages 20 to 45 with “excellent ideological qualities” who “love the fatherland,” and are “loyal” to the party’s “mission.” Mao may have had his Little Red Book, but Xi has a personalized app distributed to all 90 million CCP members, with a directory of his speeches and quizzes on his life and political thought.

His mission is to forge a singular Chinese identity that restores the nation’s ethnic Han majority to a golden age, on the basis of fealty to his party. “Xi Jinping is fundamentally a Han chauvinist with a ‘historic mission’ to make China, Han China, great again,” says Professor Steve Tsang, director of SOAS China Institute at the University of London.

And he’s willing to go to extreme lengths to do it. In China’s restive Xinjiang province, a systematic campaign of forced internment has transformed the area into a dusty expanse spotted with camps where more than 1 million Uighur Muslims and other ethnic minorities are held extrajudicially, according to the U.N. What began as a campaign to battle radical Islam in the region has mutated into an enormous project of ideological re-education. On the routes where Silk Road caravans once traveled, a sophisticated surveillance apparatus shrouds the wider populace in an AI-powered panopticon, where every action is watched, recorded and judged by algorithm.

Those who fall foul of it are sent to learn the error of their ways. Nurlan Kokeubai, 56, never found out the charges against him. But from August 2017 to April 2018, he was detained in a re-education camp close to the city of Ili, in Xinjiang province. For four hours each morning, Kokeubai says he and his fellow inmates were forced to watch videos of Xi carousing with dignitaries and overseeing military exercises. They were also ordered to memorize Xi’s eponymous “political thought” and documents from the 19th CCP Conference, where Xi removed presidential term limits to enable himself to rule for life. Those that resisted were beaten with sticks or strapped to a metal chair for interrogation. “They weren’t testing our knowledge or loyalty,” Kokeubai told TIME in Almaty, Kazakhstan, to which he has since fled. “They were just filling us with this propaganda.”

President Trump has kept mum on the Xinjiang camps as he negotiated a provisional agreement in the trade war. But when the coronavirus broke, his Administration did not hold back. “I don’t want to talk about a victory lap over a very unfortunate, very malignant disease,” Commerce Secretary Wilbur Ross said in a TV interview on Jan. 30. “The fact is, it does give business yet another thing to consider … I think it will help to accelerate the return of jobs to North America.”

Forty years after Beijing and Washington normalized relations, the two are diverging rapidly. Under Trump, the U.S. has been disentangling its firms and, yes, supply chains from China’s through taxes, tariffs and punitive investment curbs. Western investors are also cowed by ideological hurdles and looking elsewhere, given China’s market is now sophisticated, saturated and tricky to exploit. Washington has banned Huawei, the world’s biggest telecoms equipment manufacturer, from its key infrastructure and urged allies to do the same. In U.S. universities, Chinese researchers have been purged as academia, wary of espionage, lurches into Sinophobic McCarthyism. The patient optimism that colored the George W. Bush and Obama administrations has largely evaporated.

But it’s a mistake to ignore Xi’s own agency in this process. “[Last year] was a landmark in the structural shift of how the United States views its relationship with China,” says Tsang. “But the decoupling wasn’t started by Donald Trump. It was originally prepared by Xi Jinping himself.” Every one of Xi’s signature economic policies has sought to reduce China’s reliance on the U.S. and grow its own empire. His $1 trillion Belt and Road Initiative builds connectivity across Eurasia and Africa. The “Made in China 2025” campaign aims to propel China to the forefront of strategic industries currently dominated by Silicon Valley, such as semiconductors, aerospace, AI and robotics. The Chinese government has even ordered all state departments to remove foreign-made computer equipment within three years.

Xi does not stand alone, though he is surrounded by clients rather than friends. China is now more closely aligned with Russia than at any period since Mao and Nikita Khrushchev fell out in 1956. The Belt and Road Initiative is drawing nations across Asia, Africa, Europe and the Middle East into Beijing’s orbit (and often into its debt). The U.S. may have asked 61 countries to shun Huawei, but only three–Japan, Australia, New Zealand–have acquiesced. The next decade won’t be defined by an iron curtain but two blocs vying for influence within every nation that isn’t firmly in the liberal democratic or autocratic camp. And, for one side, the coronavirus is being sized up as an opportunity. Asked whether import levies on China should be dialed down given the crisis, White House trade adviser Peter Navarro demurred. “Let’s remember why the tariffs are in place,” he said.

Confronting an outbreak requires more than just an ability to throw up hospitals in a few days; it necessitates trust. And from the beginning, China’s public response to the virus has raised questions. Even multinational institutions like WHO are feeling this as the coronavirus worsens. The organization was unable to rule on the severity of 2019-nCoV following its first meeting on Jan. 22, apparently because of resistance from Beijing. (WHO referred to “divergent views.”) Notably, despite WHO’s insisting that travel bans to China would not be necessary, a dozen nations introduced stringent restrictions, including the U.S., Australia and North Korea. If you believe China’s official figures, 2019-nCoV has a fatality rate of just 2%–about the same as regular influenza and a far cry from the 50% of Ebola or the 10% of SARS. Why then, observers might well ask, has China placed entire cities in lockdown, quarantined tens of millions and mobilized troops?

Here is the downside of Xi’s system of top-down control; nobody acted until they got word from the top, and then everyone wildly overreacted in order to satisfy the leader. This was evident in Wuhan, the capital of Hubei province, where the outbreak began, and the official response lurched from cover-up to overreaction only after Xi addressed the crisis. “The full CCP apparatus didn’t kick into gear to address the coronavirus until Xi had weighed in on the matter,” says Blanchette. Notably, the President himself has kept a low profile since the outbreak began and was not seen in public for eight days after the Lunar New Year.

Now, throughout China, fear is mixing with inchoate rage. In Hubei province, people from Wuhan are ostracized. But in other provinces, people from anywhere in Hubei are shunned. Videos circulating on social media show vigilantes tooling up to protect their villages. In one video, a man in a dark jacket and wide-brimmed hat guards a bridge with a pistol. In another, a man in an orange puffer jacket sits on a table at the entrance to his village, brandishing an enormous sword. All have signs nearby with a common theme: outsiders cannot pass.

Even in Beijing, apartment building guards are checking the IDs of everyone who enters and banning those from Hubei–rent-paying tenants included. Videos emerge of Hubei residents scuffling with gas station staff who refuse them service. Sometimes mass brawls erupt when a Hubei resident tries to force himself past an improvised roadblock. “Don’t blame us for being rude if you are from Wuhan and you don’t self-quarantine,” wrote one poster on China’s Twitter-like microblog Weibo. “You should just shoot them because they are killing us!” wrote another.

The ideological revival behind Xi’s “China Dream” may have rendered the political system more decisive but also more prone to error. Under Mao, local officials were also hesitant to act until they had clear signals from the top. Rather than assess issues through a purely governance lens, China’s bureaucracy is forced to balance both technocratic and political concerns. Meanwhile nativist vigilantism spreads almost as fast as the virus.

Some questions–whether the virus becomes a pandemic (or reaches epidemic levels on two continents), how many people it infects and how many lives it takes–remain shrouded in uncertainty. But the crisis has already demonstrated that the centralization of political power under Xi has made Chinese society brittle. The question now is what it will endure before it begins to crack.

Wu’s mother was cremated the evening she died. A battered container truck arrived at 9 p.m. and packed her body in with countless others. Instead of 2019-nCoV, her death certificate simply reads “viral pneumonia.” Wu signed a permission slip for the cremation but was told her mother’s ashes won’t be released until the crisis has abated. “They say that there are more than 300 dead now,” says Wu, “but I think there are many more.” Distrust, it turns out, is infectious too.

–With reporting by AMY GUNIA/ HONG KONG