Pandemics are perversely democratic. They’re nasty, lethal and sneaky, but they don’t discriminate. No matter your age, ethnicity, religion, gender, or nation, you’re a part of the pathogenic constituency.

That shared vulnerability, and the resulting human collectivism—a universal response to a universal threat—is newly and vividly evident in the face of the now-global outbreak of the novel coronavirus known as 2019-nCoV. As of writing, there have been over 30,000 diagnosed cases and over 630 related deaths. A virus that emerged in a single city, Wuhan, China—indeed, in a single crowded market from an unknown infected animal—has now reached 23 countries, across Asia, Europe, the Middle East, and North America.

( function() {

var func = function() {

var iframe = document.getElementById(‘wpcom-iframe-4e875e7c4b5525094bb57f8722c05707’)

if ( iframe ) {

iframe.onload = function() {

iframe.contentWindow.postMessage( {

‘msg_type’: ‘poll_size’,

‘frame_id’: ‘wpcom-iframe-4e875e7c4b5525094bb57f8722c05707’

}, “https:\/\/embeds.time.com” );

}

}

// Autosize iframe

var funcSizeResponse = function( e ) {

var origin = document.createElement( ‘a’ );

origin.href = e.origin;

// Verify message origin

if ( ’embeds.time.com’ !== origin.host )

return;

// Verify message is in a format we expect

if ( ‘object’ !== typeof e.data || undefined === e.data.msg_type )

return;

switch ( e.data.msg_type ) {

case ‘poll_size:response’:

var iframe = document.getElementById( e.data._request.frame_id );

if ( iframe && ” === iframe.width )

iframe.width = ‘100%’;

if ( iframe && ” === iframe.height )

iframe.height = parseInt( e.data.height );

return;

default:

return;

}

}

if ( ‘function’ === typeof window.addEventListener ) {

window.addEventListener( ‘message’, funcSizeResponse, false );

} else if ( ‘function’ === typeof window.attachEvent ) {

window.attachEvent( ‘onmessage’, funcSizeResponse );

}

}

if (document.readyState === ‘complete’) { func.apply(); /* compat for infinite scroll */ }

else if ( document.addEventListener ) { document.addEventListener( ‘DOMContentLoaded’, func, false ); }

else if ( document.attachEvent ) { document.attachEvent( ‘onreadystatechange’, func ); }

} )();

These days, says Justin Lessler, associate professor of epidemiology at the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, “it takes only a few links to make the global population fully connected in a pandemic like this. There hasn’t been a population fully isolated from pandemic since the 15th century, when the Spaniards came to the Americas and brought smallpox with them.”

In the pre-Columbian era, civilizations could rise and thrive on one side of the world without ever being exposed to viruses, from the other. Half a millennium on, the behavior of viruses like smallpox or 2019-nCoV hasn’t changed, but the behavior of their human hosts and victims has. Of all of the things that distinguish 21st century humanity from that of earlier eras, it’s our growing state of interconnectedness that has the greatest impact on disease spread. In 2019, there were some 40 million commercial flights worldwide, carrying about 4.7 billion passengers. For a virus, that’s the equivalent of 4.7 billion dandelion spores, each a potential carrier of its DNA, drifting to wherever the air-travel currents blow them.

“Air travel contributes to the rapidity of a disease’s spreading,” says Dr. Jay Varkey, associate professor in the Division of Infectious Diseases at Emory University School of Medicine. “Think of the 2009 novel H1N1 influenza virus. It was first identified in Mexico, and it was demonstrably proven that its rapid spread to the United States and Mexico was enhanced by air travel.” From April 2009 to April 2010, the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) counted 60.8 million infections in the U.S. alone, with more than a quarter of a million hospitalizations and more than 12,000 deaths from H1N1. Globally, the CDC estimates another 152,000 to 575,000 deaths due to the virus—a decidedly wide range, but the best the Centers could do with spotty reporting from around the world.

Epidemics and discrimination

But while air travel certainly hastens the spread of disease, it by no means causes the spread. “Diseases have always been a global phenomenon,” says Lessler. “In 1918, during the [Spanish] flu pandemic, there were only ships and railroads and perhaps one or two commercial air flights, and yet somewhere between 20 and 100 million people were killed.” There were also pandemics of the bacterial disease cholera in the 1800s, when rail and steamship travel were even less extensive than they were in 1918, and air travel did not exist at all.

The fact that infectious diseases are so easily transported in from elsewhere gives them an alien quality, an otherness that can play to the worst in humans. While the disease causing the current pandemic officially goes by the decidedly anodyne name 2019-nCoV, it is often referred to in the Western media as “Wuhan coronavirus.” Ebola virus similarly takes its name from the Ebola River in the Democratic Republic of Congo, where the virus first emerged, and the 2012 pandemic of MERS stands for Middle East Respiratory Syndrome, because it was first identified in Saudi Arabia. (Tellingly, as Sonia Shah wrote recently in TIME, “HIV, discovered in NYC in the 1980s is not ‘NYC-1’ and MRSA, which first exploded in Boston, is not, say, ‘the Boston plague.’”)

This leads to inevitable—and usually undeserved—finger-pointing, with blame placed on allegedly “primitive” or “unclean” practices in the nations of origin. The 2014 Ebola outbreak was wrongly said to have been caused by people eating bat meat in Guinea, and while the disease did jump from bat to human, the epidemic was eventually traced to a single luckless girl who ate food inadvertently contaminated by bat droppings. And while live wild game—including beavers, porcupines and snakes—were indeed sold for human consumption in the market in Wuhan where the 2019-nCoV is thought to have emerged, myths have spread in the U.K. and Malaysia that the disease crossed into the human population because of a Wuhanese diet that supposedly includes bat soup and rats. The bat-soup canard has been widely discredited as an Internet-fed falsehood, and while bamboo rats are indeed sometimes consumed in China there is nothing linking them to coronavirus.

Marshaling a global response

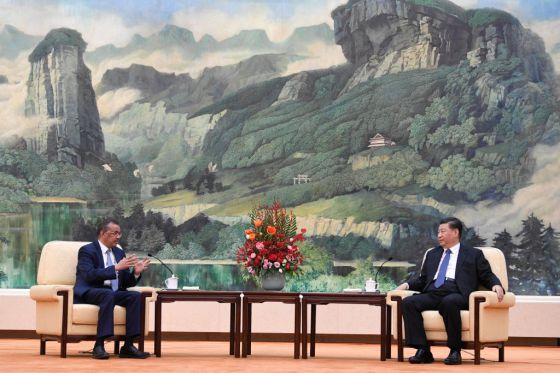

Increasingly, one of the more powerful and less probable counter-offensives against such bias may be the dry, cool-headed language of bureaucracy. On January 30, the World Health Organization (WHO) declared 2019-nCoV a “Public Health Emergency of International Concern (PHEIC),” a designation it has made only five times before, during outbreaks of swine flu, polio, Ebola, Zika, and Ebola again. A PHEIC designation does not give the WHO any enforceable authority, but it does elevate the urgency of the pandemic and helps WHO coordinate nations in implementing non-binding recommendations regarding quarantine, travel restrictions, global trade and other measures. It also encourages multinational pharmaceutical companies to work together to sequence the virus and develop treatments and perhaps a vaccine.

The impact of the recommendations depends entirely on the willingness of local and national health officials around the world to follow them, which means compliance can be spotty. But there are no countries or localities that would want to go through what Wuhan and the rest of China are experiencing, and recommendations from WHO carry a lot of persuasive weight.

Just as important, the PHEIC declaration gives WHO general-director Dr. Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus an opportunity to remind the world that any country that is the first to be struck by a disease is not some form of pandemic boogeyman, but a victim of viral chance. “This declaration is not because China is not doing what it can,” Ghebreyesus said during a press event announcing the public health emergency on Jan. 30. “It’s actually doing more than what it’s required to do. [The PHEIC] is about protecting countries with weaker health systems.”

What’s more, anyone from wealthy western countries tempted to blame pandemics on some unclean other would be better served by looking inward, because wherever life exists on the planet—which is effectively everywhere—disease can emerge. Varkey and Lessler both lay the responsibility for antibiotic-resistant strains of otherwise controllable bacterial diseases at the feet of the West, where the drugs are often overused. That makes it more likely for strains of bacteria to develop mutations rendering them immune—or at least-less susceptible—to antibiotics, and that in turn creates whole new epidemics.

“Cases of C. diff [Clostridium difficile, an intestinal infection] are common in health care settings, and those are a result of antibiotic use,” says Varkey. One particularly deleterious strain of C. diff is known at NAP-1—the NA in the name stands for “North American,” because it started in the U.S. before spreading to Canada and Europe.

It’s not just antibiotic-resistant bacteria that emerge from the West. Powassan virus, a rare tick-borne disease, emerged in Ontario, Canada in the 1950s and then traveled to New England before spreading to other northeastern and Great Lakes-region states. While the mosquito-borne Zika virus may have emerged in Africa, it changed its character and its virulence only after it spread to the west. During the outbreak of 2015 and 2016, the disease spread to 26 countries in the Americas, hitting Brazil hardest, with 1.5 million cases; Colombia, with more than 25,000 cases was next, with thousands of cases elsewhere in the region.

“All areas of the world are capable of throwing an infection out into the global arena,” says Dr. Marshall Lyon, also a professor at Emory’s Division of Infectious Diseases. “There’s not one particular disease originating in one particular place that is special in that respect.”

All that means infectious disease pandemics necessitate truly global responses, where, instead of casting blame, people rise up to protect those communities not yet infected and care for those that have been.

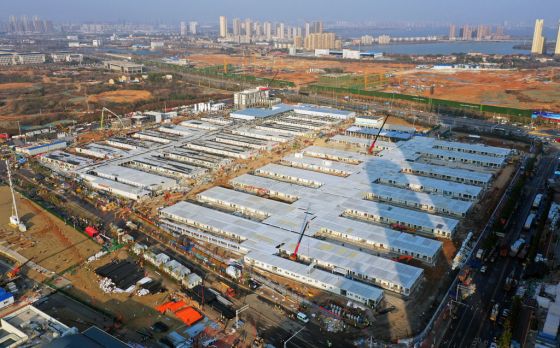

How we’ll beat 2019-nCoV

In the case of 2019-nCoV, human response has been mixed. As Charlie Campbell reported for TIME this week, fear and rage have driven some in China to act heartlessly and even violently towards those from Wuhan and Hubei province, and some analysts have raised concerns about how the Chinese Communist Party has handled the outbreak. But, on the other hand, doctors and other caregivers have staffed hospital wards and fanned out throughout Wuhan and other cities to help contain the infection, putting themselves in danger of falling ill themselves. Construction workers built two entirely new hospital buildings with capacity for 2,300 patients combined in less than a week.

Meanwhile, Pakistan, which has restricted commercial flights to China, has nonetheless offered to send a field hospital to the country to help care for the sick. Germany, which has still had only a handful of cases, has ramped up its drug development trials, with the nation’s research minister, Anja Karliczek, promising a vaccine within months.

In 2014, TIME named the Ebola Fighters the Persons of the Year, after teams of health-care workers from around the world swept into Western Africa to battle an outbreak of the disease. WHO estimates that caregivers working with Ebola patients are from 21 to 32 times more likely to contract the disease than people in the surrounding population—and during the 2014 outbreak WHO announced that more than 240 health care workers did fall sick in four African nations, more than half of whom died. The same selflessness is evidenced by the field workers who have risked—and in some cases lost—their lives vaccinating children against polio in tribal regions of Pakistan, where Taliban extremists target outsiders they suspect of spreading disease with the vaccines meant to prevent it. Something similar is true too of every worker who has ever choppered or trudged or driven into infectious hot zones to fight Zika or SARS or MERS or any other emerging diseases.

Dr. Tunji Funsho, who led Rotary International’s successful effort to wipe out polio in Nigeria, likes to tell a story about a public gathering in the country at the beginning of a seasonal round of vaccinations in 2016. Rumors were still circulating that the vaccine would sicken children and sometimes leave them sterile. So the Emir of northern Nigeria—a hereditary, religious leader descended from a ruling family, with ceremonial authority in part of the country where the rumors were especially stubborn—took the stage, promised the audience that the vaccine was indeed perfectly safe and then, to make that point clear, called for a vial of it to be brought to him. “He opened it up and drank the entire thing,” Funsho says. “After that, people believed the truth.”

Pandemics will always be characterized by their randomness, pitilessness, and power to sicken and kill. The human response, when it’s at its best, is defined by collective courage and compassion, a “not-on-our-watch” refusal to let a disease have its way with fellow humans. And to limit the impact of—and ultimately defeat—the current coronavirus pandemic, that’s exactly what we’ll need.