Around 10 days ago, Danny Zausner, chief operating officer of the USTA Billie Jean King National Tennis Center in New York City — home of the U.S. Open — received a call that would be considered inconceivable not that long ago. Local government officials wanted to know whether the sprawling 42-acre tennis complex could house a makeshift hospital for COVID-19 patients. The City’s health care system was already taxed, and the crisis was only worsening.

Zausner said officials asked about utilizing Arthur Ashe Stadium, the largest tennis stadium in the world and site of some of the sport’s most memorable moments, as a medical facility. But Ashe is actually not ideal for the purpose. It houses just one outdoor court, and the space under the stands in relatively confined. Zausner offered an alternative: the center’s indoor training facility, which during the Open hosts hospitality events, an interactive fan experience, and stores merchandise. The dozen courts offer 100,000 square feet of space. After a few site visits, the deal was done. “They’re going to be building a hospital,” says Zausner, “from scratch.”

Construction on the 350-bed facility starts this week. “This place will be a lifesaving place,” said New York Mayor Bill de Blasio at a Tuesday press event.

During the COVID-19 pandemic, the sports world has stepped up with countless acts of kindness. To name just a few: on March 27, New Orleans Saints quarterback Drew Brees and his wife, Brittany, announced they would donate $5 million to charities feeding people in need in Louisiana, where the number of cases increased 30% on Tuesday alone. The Arizona Diamondbacks have given over $1 million for supplies like food and personal protective equipment for health care workers. Tennis star Rafael Nadal and NBA vet Pau Gasol have started a drive to raise north of $12 million for Spain, their home country, which has been devastated by the outbreak.

Now, sports are moving closer to the front lines of the epidemic, as many athletic facilities around the world are being converted into temporary hospitals. During past disasters, emergency organizers have turned to sports facilities for relief: the Superdome in New Orleans, for example, became a problematic shelter after Hurricane Katrina in 2005. And following a 6.4 magnitude earthquake that struck Puerto Rico in January, relief workers distributed meals on baseball fields and track and soccer facilities. The novel coronavirus outbreak, however, is not a disaster contained to one area. All over the globe, officials been forced to canvass for extra spaces to ease the strain on existing hospital systems. Sports facilities have opened their doors to patients like never before.

Wuhan converted one of its large sports complexes into a hospital as the outbreak worsened, and others have done the same. According to the Philippine Sports Commission, two national sports complexes — one in Manila and one in Pasig City — will be turned into hospitals. The most famous stadium in Brazil, the Maracanã in Rio, is slated to become a field hospital; a temporary facility is also being set up in a Sao Paulo stadium. The health minister of Wales approved funding to construct a 2,000 bed facility at the national stadium, Principality Stadium, which has a retractable roof. Real Madrid’s stadium, Santiago Bernabéu, will store medical supplies.

In the U.S., besides the plans for the tennis center in New York, some 400 Army soldiers are helping build and run a hospital at CenturyLink Field Event Center, adjacent to the stadium where the Seattle Seahawks and Seattle Sounders play. It will house non-COVID patients to allow the area’s existing hospitals to focus on treating the disease. The Army Corps of Engineers is honing in on Sleep Train Arena in Sacramento, the former home of the city’s NBA franchise, the Kings, as a site for a 360-bed facility that would serve COVID and non-COVID patients; California governor Gavin Newsom has identified Oakland Coliseum, home of the A’s, as a potential site “surge site” if an influx of COVID-19 patients requires additional health care capacity in the state. An A’s spokesperson pledges that the organization “stands ready to do anything and everything possible to help those in need during this important time for our community.”

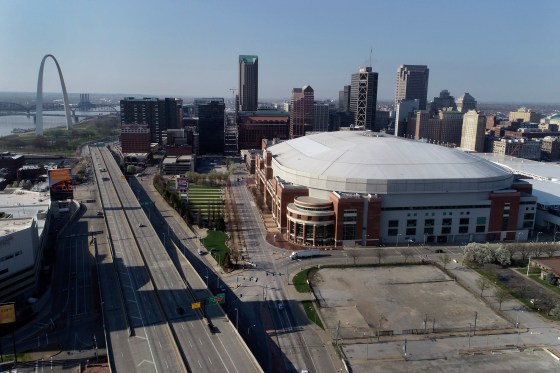

In Missouri, the governor, Mike Parson, said on Tuesday that the Missouri National Guard is considering the Dome at America’s Center in downtown St. Louis, former home of the NFL’s Rams and now-home of the XFL’s St. Louis Battlehawks, as an alternative health care site. University of Missouri officials met last week with representatives from the Army Corps of Engineers, Missouri Hospital Association, the Missouri National Guard and the state to discuss a possible overflow facility; the Mizzou Arena, home of the school’s basketball teams, and another on-campus arena, the Hearnes Center, were discussed as possibilities.

Health care providers are also using sports real estate to test for COVID-19. Testing sites have been set up outside Citizen’s Bank Park in Philadelphia, where the Phillies play, and at a spring training complex in West Palm Beach, Fla. shared by the Houston Astros and Washington Nationals. Given their size, football stadium parking lots are ideal for drive-up testing; testing has taken place at the lots of TIAA Bank Field in Jacksonville, FedEx Field outside Washington, D.C., and Hard Rock Stadium, home of the Miami Dolphins.

In New Orleans, where Mardi Gras festivities likely helped cause a rapid spread of the virus, the company that runs the Smoothie King Center, where the NBA’s Pelicans play, has given the city and state permission to use the arena floor to store masks, hazard suits, gloves and other supplies to aid overwhelmed health care workers.

Many experts believe that as COVID-19 continues to tax America’s health care infrastructure, more stadiums, arenas, and sports complexes will be put to alternative use — especially as field hospitals. “Over the next couple of weeks we’re going to see that happen,” says Fady Barmada, co-founder and president of Array Analytics, a health service group whose modeling predicts a massive shortfall of ICU beds across the country. “In a best-case scenario, we have to use as few of them as possible for as short a time frame as possible.”

Sports facilities offer scale and efficiency for providers: they can supervise many patients at once, freeing up other workers to concentrate on the most severe cases at permanent hospitals. You can fire up the concession stands to feed patients and workers. Trucks and buses can easily move people and supplies in and out of the facilities, and the stadiums and arenas come equipped with massive amounts of electrical power to keep a hospital going.

“There’s just a huge gain in practicality in using these facilities,” says Dr. Lee Kaplan, director of the Sports Medicine Institute at the University of Miami Health System who, as team physician for the Miami Marlins and the University of Miami Hurricanes, spends plenty of time in sporting venues. “They provide lodging, electricity, air conditioning — all the things you need.”

New York City, which has already turned to a convention center and a Navy ship to treat patients, certainly needs the sports space. The USTA complex, in Queens, sits close to Elmhurst Hospital, which is particularly overwhelmed by COVID-19 patients. So the city hopes to send patients with less severe symptoms for treatment at the tennis courts.

On Tuesday, Zausner, chief operating officer of the tennis center, reminded Mayor de Blasio that the U.S. Open is scheduled to begin on August 31, exactly five months to the day. The temporary hospital, however, will stand as long as needed. “We don’t know if we’re at the beginning or in the middle,” says Zausner. We’re certainly not at the end. Every bed — on a tennis court, a football field, anywhere on earth — counts.