On March 14, Kevin Hommema, an aerosol scientist at Battelle, a Columbus, Ohio-based research and development nonprofit, sent an email to his boss with a new idea: What if Battelle repurposed an older chemical decontamination technique to help health care providers decontaminate and reuse N95 masks that were in short supply across the nation?

Hommema didn’t get a response, so about 12 hours later he sent a follow-up email. Matt Vaughan, a senior vice president at Battelle, had been buried all day working on developing a rapid COVID-19 diagnostic tests and didn’t have a chance to get back to Hommema. “At 10:08 that night, he had sent a second email that was super polite, but basically said, ‘Hey Vaughan, could you pay attention?’” Vaughan recalls to TIME.

Vaughan paid attention the second time—and Battelle’s business was transformed almost overnight. The next day, the nonprofit, which is responsible for much of the technology behind Xerox copy machines, product barcodes and compact disks, launched an effort to build out and scale its old decontaminating technology to efficiently disinfect masks and other PPE. “Our team is working 24/7, and they have been since March 14 to put this system together and get it out to the communities that need it to protect the nurses, clinicians, and doctors on the frontlines who were protecting us,” says Vaughan.

Like many good ideas, Hommema’s brainchild seems obvious in retrospect. In 2015, Battelle had successfully performed for the Food and Drug Administration a chemical technique that uses concentrated, vapor phase hydrogen peroxide as a disinfectant in “emergency situations.” But the company hadn’t yet faced an emergency that would require their research be implemented in real life. Hommema, who is married to a physician and knew that health care professionals were facing a dire shortage of personal protective equipment (PPE), and especially N95 masks, simply made the connection: why not use the old disinfecting technique to decontaminate and reuse N95s today?

Three weeks later, Battelle’s technology now has the capacity to decontaminate tens of thousands of N95 respirators, the type of face mask that is the most effective in protecting a healthcare worker from tiny droplets that can transmit viruses like the novel coronavirus. The disinfecting technology—Critical Care Decontamination Systems—are now set up across the country, in some of the areas hit hardest by COVID-19, including two in New York, one in Seattle and one in Boston. Another is being built in the Chicago area.

Each of Battelle’s Critical Care Decontamination Systems can decontaminate up to 80,000 respirators a day, and the company has a total of six up and running or soon to be running. Once hospitals in the areas with the decontamination systems start providing Battelle enough used masks, the company will be able to decontaminate more N95s than existed last month in the entire U.S. stockpile in just eight days.

Hommema, who credits his wife, the OhioHealth Medical Director of Provider and Associate Well-Being Dr. Laurie Hommema for helping to come up with the idea, flagged Vaughan at just the right time. In early March, the Department of Health and Human Services estimated that in the case of a “full-blown” pandemic, the U.S. would need 3.5 billion N95 respirators over the course of a year. Officials eventually admitted that the federal stockpile had roughly 1% of that on hand. Meanwhile, American healthcare providers, facing shortages in their hospitals, had already begun reusing N95s, often for days, hiding them in their lockers, and sometimes trying to self-sanitize them with Lysol.

N95 masks are only supposed to be worn up to eight hours at a time, and should be swapped out between patients who may not have the same infectious disease. With Battelle’s system, health professionals can wear, clean and then re-wear N95s up to 20 times before they have to be thrown out. (Battelle is currently trying to determine whether the system can also disinfect surgical masks and ventilator components.)

Though the chemical process sounds complex, some of its components are very elementary. The entire sanitation process takes place inside the shipping containers you might see on the back of a semi-truck or atop a barge. Employees spread out used N95 masks on metal racks, then a set of tubes pumps a vapor into and then out of the chamber. At the beginning of the process, staff increase the humidity level inside the metal containers, so hydrogen peroxide can build up on the masks in the form of condensation—which kills both bacterial and viral agents.

Battelle’s pivot wasn’t without hurdles. First, Battelle had to get fast-tracked approval from the FDA to use the technology. On March 28, the FDA issued an Emergency Use Authorization for Battelle to decontaminate masks, but only up to 10,000 of them a day—an eighth of each system’s capacity. The next day, Ohio Gov. Mike DeWine criticized the FDA’s limited approval as “nothing short of reckless” and soon after, President Donald Trump urged the FDA in a tweet to “move quickly.” Battelle was eventually granted full FDA approval. (Vaughan was so busy working at the time, he says his 13-year-old son had to tell him the President was talking about his company.)

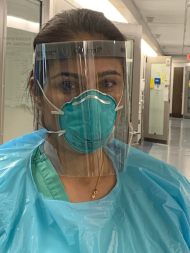

The system’s fast-tracked approval has been a godsend for healthcare providers in Ohio. Just a month and a half ago, OhioHealth Riverside Methodist critical care physician Dr. Simi Bhullar says the pandemic was forcing her to make calculations before applying a new N95 mask. “We were all trying to really focus on how we get everybody to a place where they’re routinely conserving PPE when that had never been something we had thought about before,” she says.

Since Battelle’s FDA approval, OhioHealth has received between 2,000 and 4,000 decontaminated masks each day that it can then distribute to its network of 12 hospitals, like the one where Bhullar works.

“Having access to appropriate PPE consistently is a huge relief,” Bhullar says. “I have a six-year-old and a nine-month-old at home. Knowing that I have access to the tools I need to stay safe for myself, for my patients, and for my family—I’m certainly very grateful for all of that.”

The innovation may also benefit cities around the country that don’t yet have access to one of Battelle’s Critical Care Decontamination Systems. “From a national stewardship standpoint, it’s allowed us to focus on securing the right amount of product, but not too much product so that we leave that product available to other providers in the country that maybe don’t have access to this decontamination process,” argues Chris Clinton, OhioHealth’s vice president of shared services.

In a world defined by overcrowded inboxes, Battelle’s story seems to offer a cautionary tale. Once in a while, an email—and then a follow-up email—just might save thousands of lives.