At 2:34 pm on Friday, March 13—a day after New York Governor Andrew Cuomo announced a ban on large gatherings, with the number of novel coronavirus cases in the state having tripled over the last four days—Rebecca Klassen, an associate curator of material culture at the New-York Historical Society, emailed museum director Margi Hofer. “I think we should collect an object or two to represent the pandemic,” she wrote. “What would you think if I asked around for an empty bottle of Purell, aka liquid gold?”

Eleven minutes later, Hofer emailed back: “Sure. I have a pocket-sized one if you think that will do the trick.”

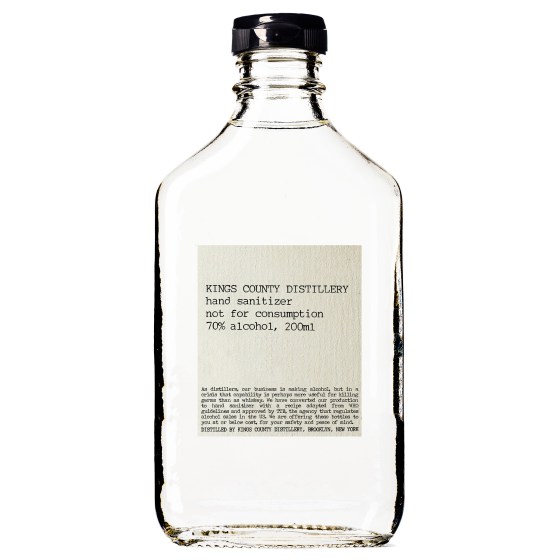

And so, the museum’s COVID-19 collecting effort began. While the New-York Historical Society has not yet officially added Hofer’s pocket-size Purell to its collection, the museum has amassed more than 200 objects and multimedia files documenting the new normal, including bottles of hand sanitizer made by distilleries and New York inmates. In April, photographer Kay Hickman and journalist Kevin Powell interviewed and photographed New Yorkers at the peak of the pandemic, and now, visitors can see the pictures and listen to interview excerpts on their cell phones in the museum’s courtyard exhibit Hope Wanted: New York City Under Quarantine—and even submit their own pandemic stories to preserve.

On Friday, six months after the World Health Organization officially declared COVID-19 a pandemic, the museum reopens its indoor galleries. The timing is apt; the N-YHS’s COVID-related collecting is the latest project within an ongoing program that began in the wake of the 9/11 attacks, to collect materials of cultural importance immediately after historic events. And the institution isn’t alone. In the last two decades, museums worldwide have carried out similar initiatives to document the aftermath of major events from natural disasters like Hurricane Katrina to social movements such as the climate strikes.

Now, with COVID-19’s historic nature firmly established, even as the world still battles the virus, the question of how it will become part of historical memory is already being answered. The artifacts many of us have accumulated in our homes right now will inform future generations about what it was like to live through this time. Here, TIME highlights some examples of what you may find in future exhibits about life during the 2020 coronavirus pandemic.

Instead of collecting the usual art or materials belonging to influential people, museums in the pandemic era are seeking out everyday people’s experiences—via TikTok and YouTube videos, Zoom screenshots and recordings, workplace emails about safety protocols, text messages about keeping busy in lockdown, and pictures of drug-store shelves stripped bare of disinfecting products.

“I want to know what’s in your emergency bag and on your shopping list,” says Anthea M. Hartig, director of the Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History.

What exactly that means varies widely. The New-York Historical Society had to act fast to acquire the cowbell that staff at the Samaritan’s Purse emergency field hospital in Central Park would ring every time they’d discharge a patient. Though life-saving equipment like ventilators can’t be collected while there’s still a critical need for them, many institutions are in touch with local hospitals about saving objects or stories from doctors, nurses and their teams. (In general, many museums are not physically collecting COVID-related artifacts while the pandemic is still ongoing, but rather asking people to email photos of objects for potential acquisition when it’s safer to collect them.)

Get your history fix in one place: sign up for the weekly TIME History newsletter

For museums nationwide, documenting COVID-19 has been inseparable from documenting the ongoing Black Lives Matters protests. At the Museum of the City of New York, a social media open call for images of “a socially-distanced NYC” and scenes of activism drew nearly 20,000 images from professional and amateur photographers. Some are now on display in New York Responds, a new outdoor exhibit of photos and stories of pandemic life. One of the photos, taken by street photographer Clay Benskin, captures a protester doing a handstand in front of a line of NYPD officers outside City Hall on the evening of July 1.

The Anacostia Community Museum in Washington, D.C., issued an online call-out for stories from both the pandemic and this year’s social justice protests. It has garnered submissions from across the country, including from frontline workers like an Atlanta UPS driver who expressed her gratitude for customers who thanked the people who kept the delivery economy going. Melanie A. Adams, director of the museum, says the goal is “to tell the story of everyday people.”

The Mercer Museum in Doylestown, Penn., received cell-phone video of a violinist playing in the parking lot of a senior housing complex and is saving copies of Neighbor to Neighbor COVID TIMES, a newsletter filled with information about the pandemic’s effects on local businesses and interviews with locals on how they are surviving.

The Museo Diocesano Tridentino in the northern Italian city of Trento pivoted from its daily work preserving early Catholic history to preserving the objects that outfitted Italians’ new sanctuaries during lockdown. When Lorenza Liandru curated photographs for an outdoor exhibit that now lives online, she started with one of her own stove-top coffeemaker, which had become “a symbol of the lost ritual of the coffee break with friends, colleagues, family.” Other subjects ranged from a terrace that allowed a woman “to feel [like] part of the world again” to games that provided a distraction from the grim news cycle.

Some of the most powerful visuals are analog. Tanya Gibb, who teaches third grade in Los Angeles, has been keeping a bullet journal for three years, and realized midway through what she thinks was a case of COVID-19 that she was documenting history. In the boxes that had previously recorded commitments like parent-teacher conferences or her twin sister’s birthday tea, she wrote “STILL SICK.” She was briefly hospitalized in March and re-admitted a month later, and had to undergo emergency surgery to save her eyesight. Days after her release from the hospital, she noticed one of her favorite museums, the Autry Museum of the American West, had posted a Facebook callout for submissions, and she emailed a picture of her journal.

She explained her rationale to TIME: “What would people want to see 100 years from now when they want to see what things were like? A diary of someone living.”

Masks, a signature of the new normal, will definitely be covered in future exhibits on the COVID-19 pandemic. Among the photos of homemade masks that people submitted to the Autry Museum is one made by a hair stylist for the clients she couldn’t see during the California stay-at-home order last spring; one with ruffles and a matching head-wrap sewn to represent the designer’s West African heritage; and masks that strangers sewed for strangers via Auntie Sewing Squad, an online community of hundreds of people nationwide who have sewn more than 80,000 masks for underserved populations, such as farm workers, incarcerated persons and victims of domestic violence.

But some places are collecting less tangible artifacts. To help future scientists track how we got here, archivists at the Library of Congress are collecting data from Johns Hopkins University’s Center for Systems Science and Engineering (CSSE), which runs a COVID-19 dashboard; snapshots from GISAID, which aggregates genomic data from labs worldwide during pandemics; and capturing analyses from platforms like Nextstrain, which are mapping the mutations of the virus and its transmission. A Web Archiving team is also preserving websites that include information about the origins of the novel coronavirus, the spread of infection and containment efforts.

The Library of Congress has also acquired photographs from Camilo José Vergara, who documents life in low-income neighborhoods, including scenes such as the “BE WELL” message on the marquee of the indefinitely-closed Apollo Theater in Harlem; pictures of residents who died of COVID-19 in the Corona neighborhood of Queens, N.Y.; and a barber giving a customer a haircut on a Newark, N.J., street. On Wednesday, the Library announced an additional effort to collect photos documenting a wide range of individuals’ experiences with the pandemic.

Six months after COVID-19 lockdown orders closed down museums, these cultural institutions face a long recovery themselves, and the online outreach has helped them reinvent themselves. Curators hope these collecting efforts help the world see museums not only as buildings, but also as online communities in which citizens play a key role.

“We just want to make sure people know we’re recording history now. We don’t have to wait until history is documented. And it’s actually better when more voices are involved,” says Tyree A. Boyd-Pates, an associate curator of Western History at the Autry Museum of the American West, who is spearheading its Collecting Community History Initiative.

A history of the pandemic that includes those voices, and the objects they donate to museums, will play a key role is helping to establish a more inclusive future vision of American history. And, some museum professionals say, they can already help donors imagine a more inclusive present. Such documenting efforts take people out of their own experiences so they can “understand others in different situations,” says the Smithsonian’s Hartig. “My hope is it helps build empathy and compassion.”