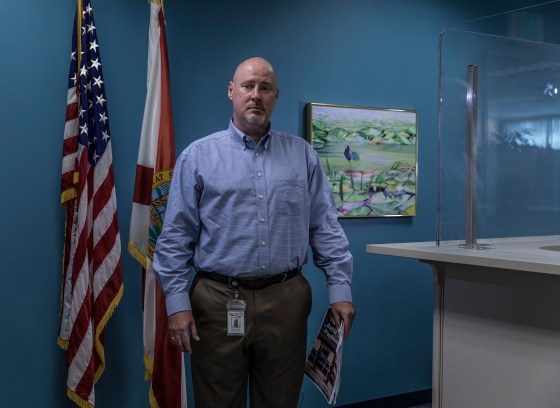

After months of watching commenters flood his office’s social-media posts with voting myths and fielding calls about election conspiracies from constituents, Brian Corley finally got fed up. In July, the supervisor of elections in Florida’s Pasco County decided to shut down his office’s Facebook and Twitter accounts to stop false claims from spreading. “I just got tired of the misinformation and the partisan bickering back and forth,” says Corley, a Republican with 13 years on the job. “I saw no value in it as an election administrator.”

If 2016 showed how foreign operatives were exploiting social media to influence the U.S. election, the lesson of 2020 is already clear and even more worrisome: the greatest threat to a credible vote is homegrown. From the White House on down, Americans have taken a page from the Kremlin’s playbook by weaponizing misinformation online to advance their political goals. Election officials like Corley are struggling to break through an avalanche of falsehoods about mail-in ballots, doubts about the integrity of voting systems and skepticism about the validity of the results.

No one has done more to sow suspicion or spread lies than President Donald Trump, whose aggressive attacks on mail-in voting and false allegations of widespread voter fraud have capitalized on fear and uncertainty about holding a presidential election in the midst of the COVID-19 pandemic. On television, at rallies and on Twitter, Trump has falsely claimed that mail-in ballots “lead to massive corruption and fraud,” that foreign powers will “forge ballots” and that the “only way we’re going to lose this election is if the election is rigged.” He has falsely implied that ballots are being sent to undocumented immigrants in California and even suggested delaying the election, which he has no authority to do, until Americans can safely vote in person.

None of this is new, exactly. As a candidate in 2016, Trump pushed baseless claims of voter fraud, including that hordes of dead people and noncitizens would vote for Democrats. Now, with the weight of the most powerful office in the world, his allegations are being parroted by federal and state officials, GOP activists, local campaigns, small-town radio shows and national media outlets. Vice President Mike Pence has backed up his unfounded claims, and Attorney General William Barr has alleged that mail voting “opens the floodgates to fraud.”

Election administrators from both parties, as well as nonpartisan officials in Trump’s own government, insist voting by mail is safe. The FBI says it has found no evidence of coordinated fraud with mail-in ballots and emphasized such a scenario would be very unlikely. “It would be extraordinarily difficult to change a federal election outcome through this type of fraud alone,” a senior FBI official told reporters in an Aug. 26 briefing.

But a claim doesn’t have to be true to affect an election. U.S. national-security agencies and social-media companies, which spent the past four years working to weed out false claims perpetuated by foreign adversaries, say the domestic disinformation this year presents a new challenge. Because of the constitutional right to free speech, it can be nearly impossible to police bad-faith claims, whether the speaker is an Internet troll or the Commander in Chief.

The result threatens not only the perceived legitimacy of this election but also Americans’ broader faith in U.S. democracy. “We have seen already that the President’s rhetoric is affecting the confidence that voters have in vote-by-mail, particularly, and also in elections in general,” Sylvia Albert, director of voting and elections at Common Cause, testified to Congress on Aug. 4. Gallup found last year that 59% of Americans are not confident in the honesty of the nation’s elections, third worst among the world’s wealthy democracies. While Trump and his allies have propagated misinformation about voting, the Gallup poll found that Trump’s critics are most distrustful: 74% of those opposed to the U.S. leadership reported a lack of confidence in the honesty of American elections. The Trump Administration’s attacks on the Postal Service exacerbated the problem, raising the question of whether the agency is capable of delivering ballots before state deadlines.

Even as officials scramble to fight back by explaining that voting by mail is secure, they worry about the stakes for the nation. The prospect of misinformation drowning out credible facts and eroding voters’ faith in elections “keeps me up at night,” says Corley, the Pasco County Republican. “It’s tough to put the genie back in the bottle.”

The threat is an order of magnitude greater now than four years ago. In 2016, a hostile foreign adversary tried to sway Americans to vote for one candidate over another; this year, that candidate is calling into question the integrity of the vote itself.

Trump’s fearmongering about the need to fight voter fraud has given new life to decades-old tactics like voter-roll purges, stringent voter-ID laws, “poll watchers” who try to intimidate people from casting ballots, and other measures that reduce turnout. “2016 was the ‘fake news’ election, but 2020 makes it look like nothing in comparison,” says Samuel Woolley, project director for propaganda research at the Center for Media Engagement at the University of Texas at Austin. “This infrastructure that has been scaled up since politicians started figuring out social media has now become concretized under Donald Trump down to the state level, the city level. It’s the democratization of propaganda.”

Last month, former Nevada Republican Senator Dean Heller claimed without evidence that a new state law, which would send every registered voter a ballot in the mail, would allow Nevadans to vote twice. “They’re going to allow anonymous people to walk into any home, any facility, to help you fill out your ballot and take it with them,” Heller said, echoing arguments made by the Trump campaign in a suit seeking to block the law. Heller’s claims were repeated in television interviews and widely shared on social media, even as the state’s Republican secretary of state, Barbara Cegavske, tried to reassure voters such claims weren’t true.

Trump’s rhetoric has also been adopted by Republican candidates. “Election fraud should concern each and every voter in this country,” wrote Margaret Streicker, a Republican running in Connecticut’s Third Congressional District, in a post shared more than 100 times on Facebook. Nicole Malliotakis, a Republican running in New York, took it up a notch, paying for Facebook ads claiming she had “stopped the liberal Democrats’ plan to automatically register illegal aliens to vote in our elections.”

The purpose of such claims is hardly subtle. In early April, Georgia state speaker of the house David Ralston said the quiet part out loud when he argued that if the state allows mail-in ballots, it “will be extremely devastating to Republicans and conservatives” because it “will certainly drive up turnout.”

This combination of disinformation, uncertainty and valid concerns over the logistics of holding an election during a pandemic also has many Democrats on edge. “The Trump Administration is a corrupt Administration,” Berthilde Dufrene said on Aug. 28 at a racial-justice protest on the anniversary of the 1963 March on Washington. “I see what they are doing with the post office and voter suppression, so I am concerned that they will cheat, they will steal, they will lie to keep this man in power.”

These fears were worsened by Trump’s recent promise to send law enforcement to the polls to monitor for voter fraud. “We’re going to have sheriffs, and we’re going to have law enforcement, and we’re going to have hopefully U.S. Attorneys,” Trump said on Fox News on Aug. 20. The President has no control over local law enforcement, yet the mere threat could depress turnout if voters believe it.

Voter fraud is exceedingly rare in the U.S., according to a 2017 Brennan Center for Justice review of more than a dozen studies. A Trump-appointed commission disbanded in 2018 after it was unable to find evidence of widespread voter fraud. “The truth is that after decades of looking for illegal voting, there’s no proof of widespread fraud. At most, there are isolated incidents–by both Democrats and Republicans,” veteran GOP election lawyer Benjamin Ginsberg wrote in the Washington Post on Sept. 8.

Yet Trump’s claims have found a willing audience in his party. The GOP has long promoted the idea that fraud is ubiquitous in order to support legal efforts to restrict ballot access, which disproportionately affect voters of color who tend to vote Democratic, and to justify a need for close election monitoring. While both parties regularly use poll watchers, this year will mark the first presidential election in decades in which Republicans will have the freedom to pursue their poll-monitoring plans without prior approval from a court, after a federal consent decree that limited the Republican National Committee’s operations ended two years ago. The consent decree had its roots in voter intimidation. It was put in place by a federal court when the party was accused of menacing minority voters in the 1980s with a “National Ballot Security Task Force” in New Jersey. “We were really operating with one hand tied behind our back,” Trump deputy campaign manager Justin Clark told the Conservative Political Action Conference this year, detailing how Republicans planned to leverage an army of 50,000 volunteer poll watchers in 2020.”There’s all kinds of ways people can steal votes,” said Clark. “We are going to have scale this year. We’re going to be out there protecting our votes and our voters.”

The misleading claims promoted by Trump and other politicians have dominated national headlines. But their effect at the grassroots level is no less important.

In Davenport, Iowa, Roxanna Moritz, a Democrat who serves as the Scott County auditor, has decided not to bother with social media as a primary method of communicating information to voters. Misinformation is too rampant. In one Facebook post, a man shared a photo of an address with seven absentee-ballot requests, claiming this was “their plan to rig the election” and calling the applications a “danger” to democracy. Moritz looked up the address and found a simple explanation: there were seven voters registered to that address.

“Ten years ago, perhaps your normal citizen would get a lot of their information from their local news channel, but now they get most of their information from cable news channels,” says Moritz. “Whatever the narrative is from the national level is how they’re driven to receive their information.”

The constant onslaught of misinformation about mail-in ballots led to a trend this summer where users who said they were Trump supporters posted videos of themselves throwing their absentee or mail-in ballot requests in the trash and encouraged others to do the same. This was especially frustrating for election officials in states that have long offered mail-in voting, like Colorado, where counties began using it for some elections in 1993. “I can no longer listen to the rhetoric that Colorado’s mail ballot system is at risk in the upcoming general election,” Fremont County clerk Justin Grantham, a Republican, wrote in an op-ed. “I feel it is my duty to assure you that your right to vote is protected and secured.”

According to an August WSJ/NBC poll, just 11% of Trump supporters said they planned to vote by mail, compared with 47% of supporters of Democratic nominee Joe Biden. State and local officials are trying to explain to Republican voters that mail-in ballots are safe and legitimate, often contradicting the President’s words. In one case, a mailer sent to GOP voters in North Carolina by the Trump Victory Fund featured Trump’s face and a partial quote from one of his tweets asserting, incorrectly, that voting absentee is secure, while voting by mail is not. The mailer included the part of Trump’s tweet declaring that “absentee Ballots are fine” but blurred out the rest of it, which read, “Not so with Mail-Ins. Rigged Election!!! 20% fraudulent ballots?” The confusion forced Darryl Mitchell, chairman of the Johnston County Republican Party, to post on Facebook, reassuring voters that the mailer was real. But in the comments section below, voters insisted they’d vote in person.

A lot of the canards and falsehoods being spread about 2020 have targeted Black and Latino communities. That was true in 2016 as well: according to a Senate Intelligence Committee investigation into Russia’s Internet Research Agency released last year, “no single group of Americans was targeted by IRA information operatives more than African-Americans.” Foreign operatives stoked anger over police brutality and economic inequity, often pretending to be Black Lives Matter activists.

These tactics are still in use today. Far-right Republican Laura Loomer’s “Twitter army” used messaging that was “squarely targeting Black and Latino voters,” according to an analysis shared with TIME by Win Black/Pa’lante, a group that focuses on combatting disinformation targeting these communities. Accounts supporting Loomer, a congressional candidate in Florida, did so by seeding false claims using the hashtags #JohnLewis, #JimCrowJoe and #BlackLivesMatter. Misinformation is “the next major barrier to the right to vote for Black and Latino people. We see it in the same trajectory as a poll tax or a literacy tax,” says Andre Banks, a co-founder of Win Black/Pa’lante. “There’s a sustained campaign around the election now where you have all the bad actors–foreign agents, trolls, all the way to the U.S. President at the top–drowning out all of the attempts to help people get the real information.”

Targeted misinformation campaigns have proved effective. More than 35% of registered voters say they are not confident the election will be fair, according to an August Monmouth University poll. Republicans say the problem is voter fraud; Democrats say it’s voter suppression. And while there are reasons to worry that every American will not have access to the polls, both concerns underscore the task that election officials now face. “If the perception is there, then people believe that it’s a fraudulent election,” Kim Wyman, the Republican secretary of state in Washington, told TIME in June.

Officials are countering with the facts. The National Association of Secretaries of State launched a social-media campaign with the hashtag #TrustedInfo2020 to amplify credible sources of voting information. The Center for Internet Security, a nonprofit that helps governments share information on cyberthreats, is working with the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) and other U.S. agencies on a “Misinformation Reporting Portal” where election officials can flag suspected false claims and get a quick response from social-media platforms. “Perhaps the biggest challenge that we face as a nation going forward,” the group’s president, John Gilligan, told lawmakers on Aug. 4, “is how we address the impact of mis- and disinformation on elections.”

Social-media companies have belatedly begun to address the problem, with Twitter taking the most aggressive actions. On Aug. 23, after the President tweeted multiple false claims about mail-drop boxes, including that they would make it possible for people to vote multiple times, Twitter obscured his tweet and added a label saying that it had violated Twitter’s rules on “civic and election integrity.” To read the presidential tweet, users had to click on the message.

Facebook says it is labeling voting-related posts so users are warned before sharing potentially misleading information. It also announced that it will block new political ads the week before the election, which critics say is too little, too late. This comes after a scathing civil rights audit of the company’s policies in July. “Ironically, Facebook has no qualms about … limiting misinformation about COVID-19,” the report found, “but when it comes to voting, Facebook has been far too reluctant to adopt strong rules to limit misinformation and voter suppression.”

Ultimately, whether Americans believe November’s election to be free, fair and valid is being challenged by one of the two men on the ballot. Four years ago, Russia subverted American democracy with a campaign to elect Donald Trump. This year, the Kremlin is taking its cues from him. On Sept. 3, DHS issued an intelligence bulletin warning that Russia is once again seeking to undermine faith in the U.S. electoral process. Among its methods? “Amplifying criticisms” of “the integrity of expanded and universal vote-by-mail, claiming ineligible voters could receive ballots due to out-of-date voter rolls, leaving a vast amount of ballots … vulnerable to tampering.” Not much question where the Kremlin came up with that.

With reporting by Brian Bennett, Mariah Espada and Abby Vesoulis